In the latest dearantler show we attempt to convey the indescribable allure that the desert has for us. My deer relatives, accustomed to the nourishing bounty of Southern California's oak woodlands and chaparral-covered hills, turn their ears away whenever I sing the desert's praises. E+J tell me that their human brethren often greet them with similar disinterest, asking questions like: "What's so special about the desert? Isn't there just a whole lot of nothing out there?"

As desert rats we could choose the cynical route, throw our arms (and hoofs) up and declare that you either get the desert or you don't. But then we remember that we didn't always get what it was all about either, and so our minds turn to Senegalese poet Baba Dioum's wise words:

In the end, we conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught.

In Notorious/Glorious we acknowledge the dichotomy that the desert conjures: it is seen as notoriously uninteresting, inhospitable or hostile by many, while others see its simplicity, starkness and want for life as glorious. For those of you in the "notorious" camp, we hope to open a door into appreciation of this harsh and elemental landscape. For the smitten among you, we invite you to join us as we celebrate the desert through art and words. And for the Hitchcock fans out there, as with all past shows, this one borrows its title from one of Hitch's films -- one really worth watching or revisiting.

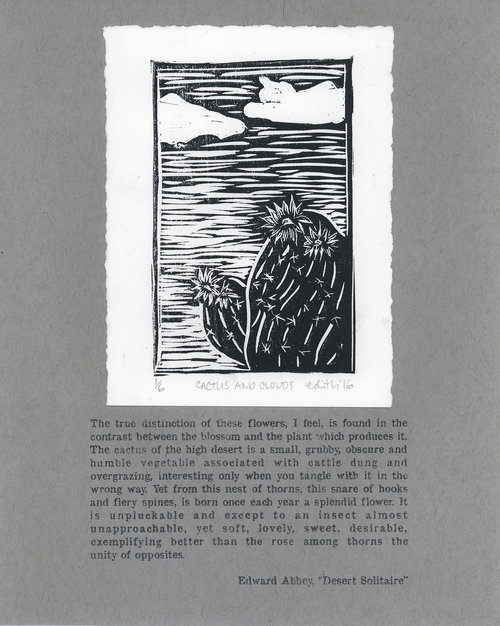

Cactus and Clouds, by Edith de Guzman

edward and everett - bringing together two voices of the desert

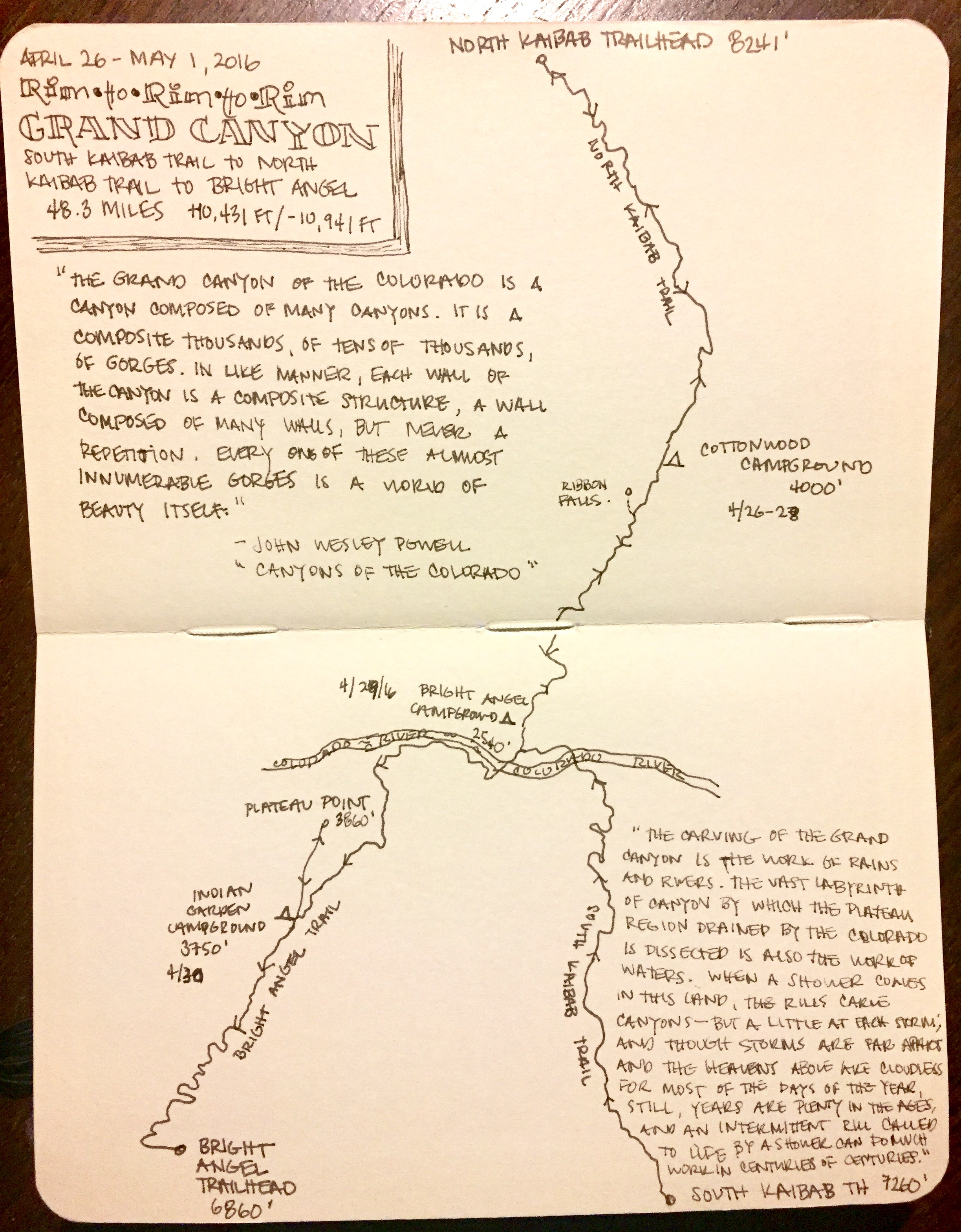

Edith's series of six prints pays homage to two desert icons: Edward Abbey and Everett Ruess.

Everett Ruess was a young artist, writer and bold vagabond who mounted mostly solo expeditions to uncharted lands of the West -- California's coast, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and the desert lands of the Southwest. Between 1930 and 1934, Ruess spent months at a time traveling on horse or burro to explore the nooks and crannies of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico, consistently writing thoughtful accounts of his experiences and encounters in journals and letters to family and friends. He produced woodblock and linocut prints, as well as paintings, which he traded and sold to fund his travels. As a precocious young man from a supportive family that placed great value on the arts and self-expression, Ruess had no qualms about literally appearing on the doorsteps of some of the day's most influential artists, consequently spending time learning from Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange and Edward Weston. Ruess disappeared in November 1934 while exploring the canyons of southern Utah. He was just 20 years old. His disappearance has fueled decades of interest in his story, prompting the curious to form theories, organize search parties, and write about the young man's travels and mysterious disappearance -- contributing to his solid legacy as a legend of the American desert.

Edith's linocut prints are an homage to Ruess's prints. Ruess employed an economical style to craft evocative compositions that convey a great deal with minimal detail.

Edward Abbey was an author and environmental activitist whose poetic eloquence and stinging wit brought attention to the disregard and exploitation that much of the arid American West has long been subjected to. With an unapologetic style, Abbey's writing reminds us that the fate of wilderness protection hangs in precarious balance and is a task that falls on all those who love and respect these lands.

The six prints include solvent-transferred excerpts from one of Abbey's best-known works, Desert Solitaire -- an autobiographical work informed by the author's experiences as a park ranger in Utah's Arches National Monument in the 1950s. With wide-ranging reflections about the beauty and immediacy of life in a harsh and hostile land, Abbey advises readers of Desert Solitaire with the following words:

Do not jump into your automobile next June and rush out to the canyon country hoping to see some of that which I have attempted to evoke in these pages. In the first place you can't see anything from a car; you've got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail you'll see something, maybe. Probably not. In the second place most of what I write about in this book is already gone or going under fast. This is not a travel guide but an elegy. A memorial. You're holding a tombstone in your hands. A bloody rock. Don't drop it on your foot -- throw it at something big and glassy. What do you have to lose?

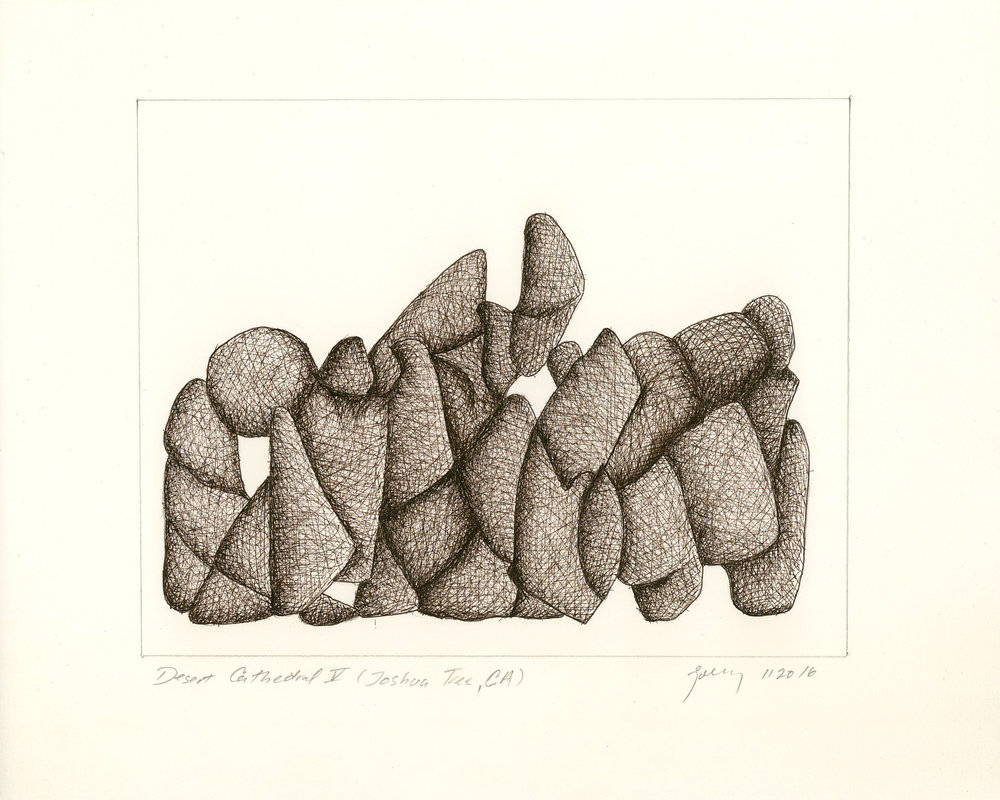

Desert Cathedral V (Joshua Tree, CA), by Jolly de Guzman

desert images - 18 pen and ink drawings from joshua tree, saguaro and grand canyon national parks

Jolly's series of 18 pen and ink drawings presents the desert in its most elemental forms. Each drawing is composed entirely of cross-hatched lines and highlights the stark beauty, individuality and isolation of the desert's features. In the desert, time stands still. As a visitor to this land, if you stop and listen you are at once called into contemplation, as though visiting a temple or cathedral. This spiritual feeling is not confined to the desert's living inhabitants -- like the Joshua trees, saguaros and beaver tail cactus in this series. Here, the rocks too elicit awe, their dynamic forms melding together like a choreographed dance paused in time and space.

Jolly engages in a meditative process to create this style of drawing -- a process that matches the introspective meditation that a long, quiet visit to the desert evokes. Within the series of 18 are four mini series, each presenting a different feature. The title of each mini series reflects the impact this land has on a visitor open to experiencing it in its full glory: An Important Occasion, Desert Cathedral, Cactus Love, Without Words.

And with that, we at dearantler find ourselves without words. Lucky for us -- and you -- winter is nearly here, and with it, desert-exploration season is in full swing. We hope to see you among the cacti and sand washes soon.