Death Valley National Park is a vast land full of surprises waiting to be discovered and explored. From the lowest point in North America at Badwater Basin (282 ft. below sea level) to Telescope Peak (11,049 ft.), Death Valley encompasses multiple mountain ranges, valleys, and countless canyons that offer a giant playground for exploring fascinating geology, jaw-dropping terrain, and interesting human and natural history. As the largest national park outside of Alaska, it offers limitless opportunities for exploration and is one of our favorite places to visit.

One of our destinations on this particular trip, which we took in late November, was the site of a remote plane crash that occurred in January 1952. The plane, en route from Idaho to San Diego, was a Graumann DC-16 Albatross owned and operated by the CIA. Six people were on board. When one of the engines failed, the pilot and five passengers parachuted to safety while the plane continued along its trajectory, crashing shortly thereafter on a steep slope in the Cottonwood Mountains, in the western part of the park. The site receives few visitors each year, no doubt owing to the fact that it is a cross-country and trailless route with challenging terrain that gains and loses elevation throughout.

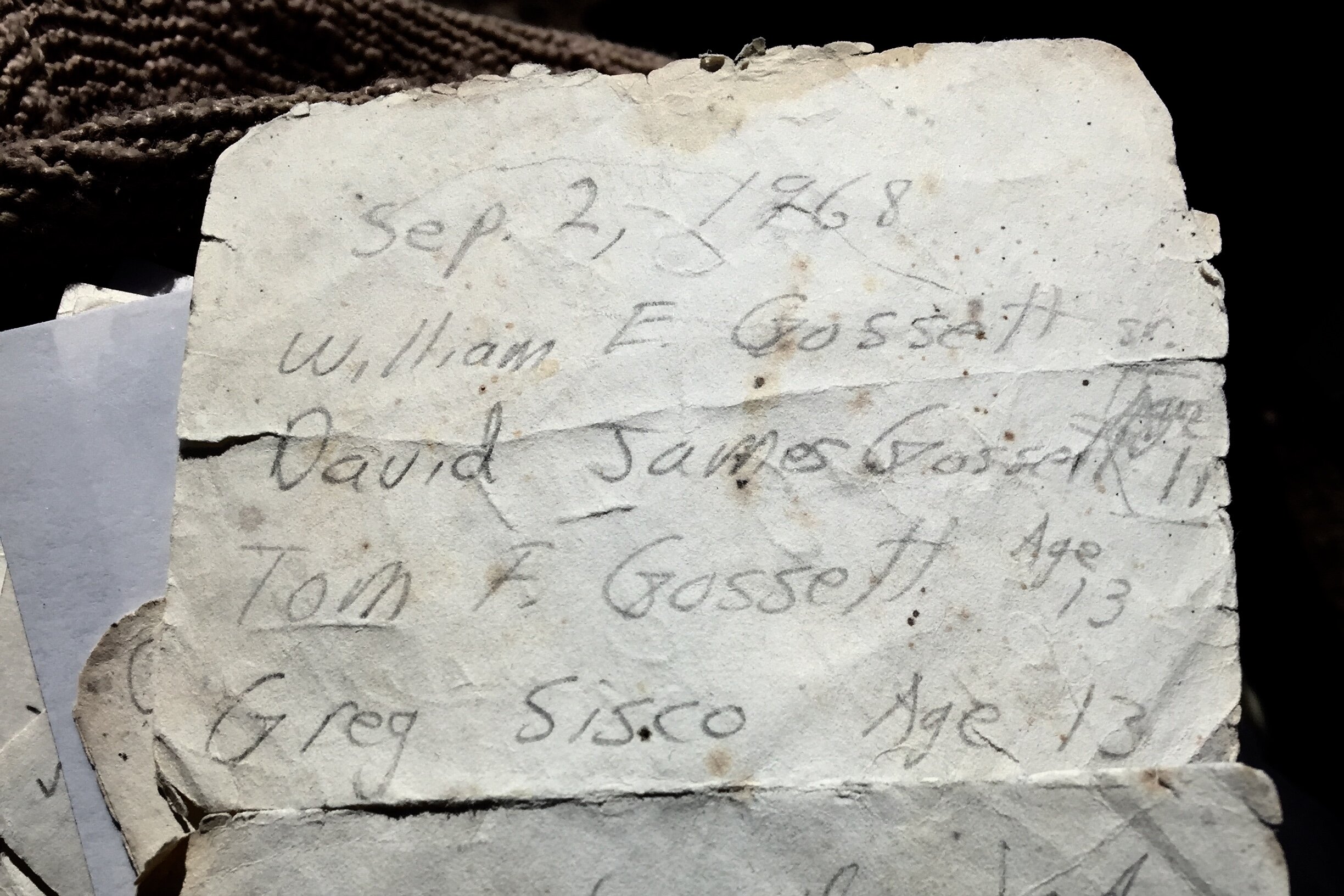

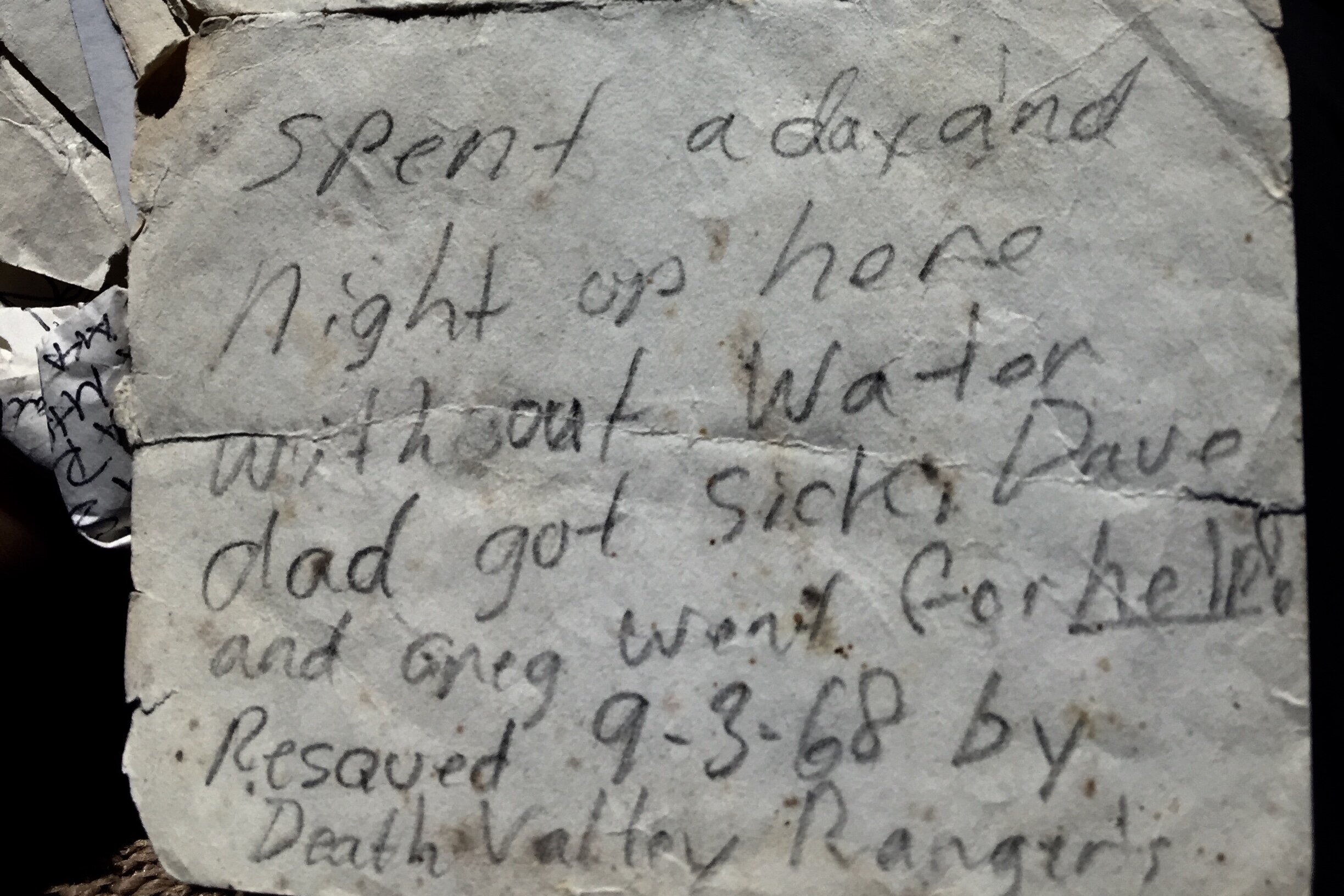

The hike begins at Towne Pass, where a pullout provides a place to park. The route-finding begins right away, with an ascent of about 400 feet up a lava field, which gets the heart rate pumping immediately. Once you reach a ridge, the first views open up and continuously improve as you follow the ridge north north-west. The plane crash site becomes visible from the ridge, and seems almost within reach just across the canyon. In reality, a challenging trip and several hours’ worth of negotiating the trailless route lie ahead. Staying on the ridge, you hug the mountain side above Dolomite Canyon until finally reaching Towne Peak (7,269 ft.), the highest point in the Cottonwood Mountains. The last steps before reaching the peak suddenly open up views to the west, revealing the majestic, snowy peaks of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. A trail register inside an ammo box contains hiker registrations that go back to the year 1967. We enjoyed lunch while reading through this historic archive. We were only the seventh party to sign the register in the prior 12 months.

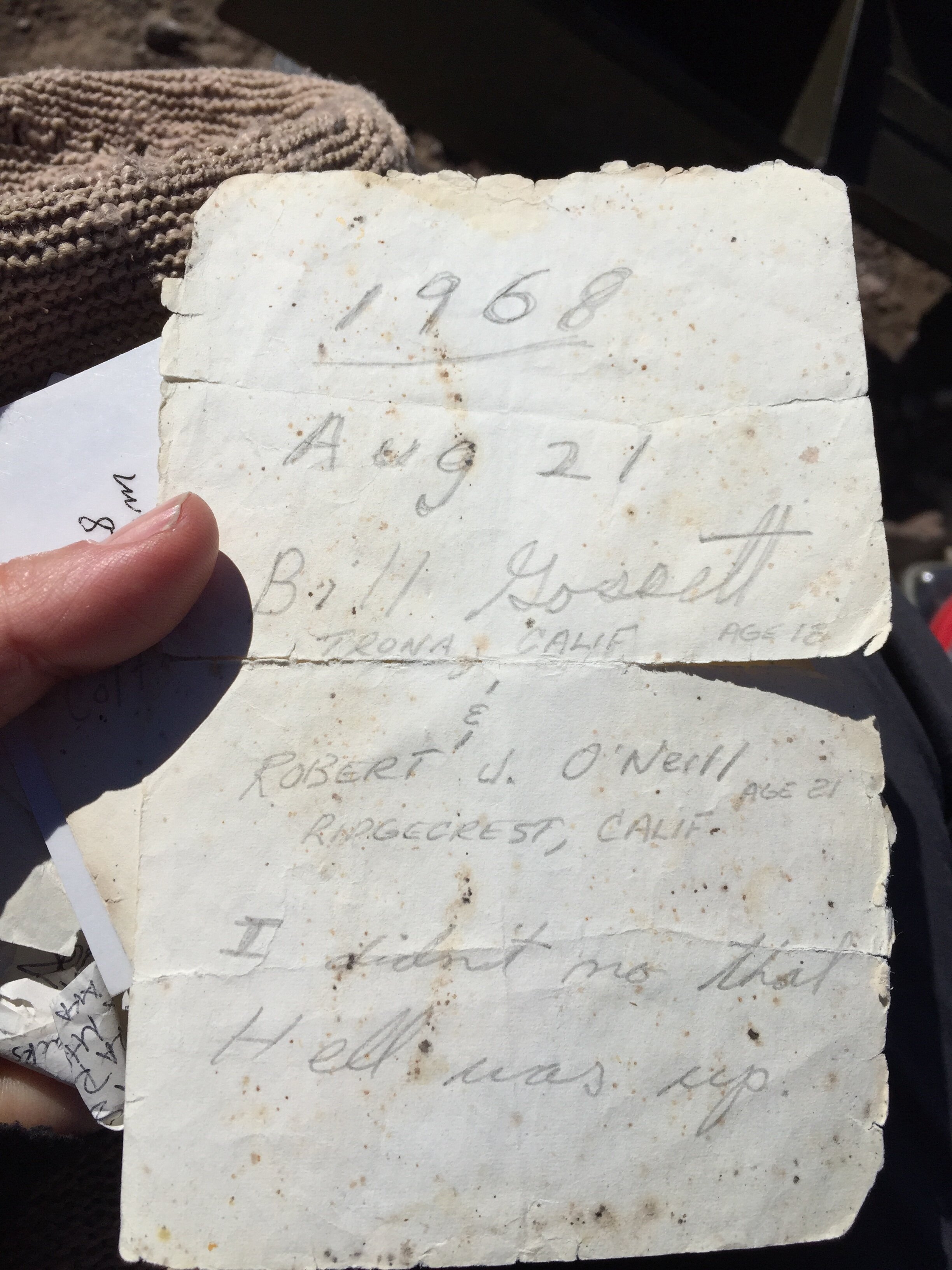

From the summit it’s about a 1-mile hike to the plane crash site, which requires about a 1,000-foot drop in elevation. Another ammo box can be found just above the final descent to the plane. The ammo box contains an old canteen full of water, and a few emergency food items including a bag of long-expired dehydrated food. The trail registry has even fewer hikers’ names than the registry at Towne Peak — only a few fools intrepid enough to go this far! The final descent of a couple of hundred feet of elevation is extremely precarious and requires traversing a slope with loose footing — ropes would be useful. There is plenty of opportunity to imagine oneself sliding down to the canyon bottom and joining the thousands of bits of plane debris that have accumulated hundreds of feet below over the past few decades. The irony of the very real possibility of dying on the hike while the plane’s passengers survived was not lost on us.

Though the fuselage is rather mangled from the crash, the plane is in remarkably good condition and the wide debris field is interesting to explore. The crash site is scenic and photogenic, overlooking Panamint Valley and the park’s vast and beautiful landscape.

We returned along the same route, once again requiring ascending and descending up and down the ridge and lava fields. The hike makes for a long, exhausting, but rewarding day, and should only be attempted with plenty of daylight and by sure-footed hikers. We assumed a 1 mph rate due to the challenging terrain, and were not far off in that estimate. All told, the 10-mile hike took us about 10 hours including breaks.

We arrived back at the car about 30 minutes after sunset, and just before needing to take out our headlamps. We had seen no one the entire day, but when we got down there was a cyclist arranging his panniers in the pullout where our car was parked. We asked him where he was going and he said he was biking from Montreal to San Francisco and had another 10 miles of cycling to do that evening, in the dark — sharing this with us in good spirits, like it was no big deal. What a way to put our feeling of exhausted accomplishment into perspective!