INQUISITIVE HIKER: “Hi, Sierra! I have a question for you. The John Muir Trail and Pacific Crest Trail get lots of attention, but what other trails do you recommend for hikers hungry to explore your neck of the woods? Maybe a shorter trail that offers something unique?”

SIERRA NEVADA: “Hello, Sierra hiker. While there are literally hundreds of options to explore me, there is a trek that I would recommend, one which traverses me from west to east and incorporates sections of the John Muir and Pacific Crest trails: it is the High Sierra Trail. Along the way, you will explore much of what my range has to offer — varied flora, fauna, geology, and even some interesting human history.”

When the Sierra speaks, it’s hard to argue. The HST is a historic traverse of the Range of Light from the verdant and gentle lands at Crescent Meadow in Sequoia National Park’s Giant Forest, to the rugged, weather-beaten escarpments of majestic Mt. Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous U.S. So without further ado, we decided to hike the High Sierra Trail with our pal Torin and see this wonderful stretch of land with our own eyes.

The HST’s preservation as a wilderness journey is a great and prescient gift given in the 1920s and 30s to future generations. But before we go down that historical rabbit hole and get romantic, let’s talk logistics. Two hurdles have to be overcome before hitting the trail: 1) securing a permit, and 2) figuring out transportation to/from the two trailheads, located on opposite sides of the range and approximately a 6-hour drive apart.

Torin submitted a permit request in March and we crossed our fingers. The HST is justifiably popular, and in order to provide opportunities for solitude as required by the Wilderness Act, there is a strict daily quota from May to September. Our request was granted, which we were very grateful for — though our awarded permit was for the lowest number of hikers we listed (3, when we requested 7) and our starting date was the fourth and last preference we listed. But hey, beggars can’t be choosers and we were thrilled we got a permit! And it turns out that the dates of our permit positioned us to conclude our hike with an ascent of Mt. Whitney under the full moon — an epic opportunity to experience the beauty and stillness of this alpine landscape at night and arrive to the summit in time for sunrise.

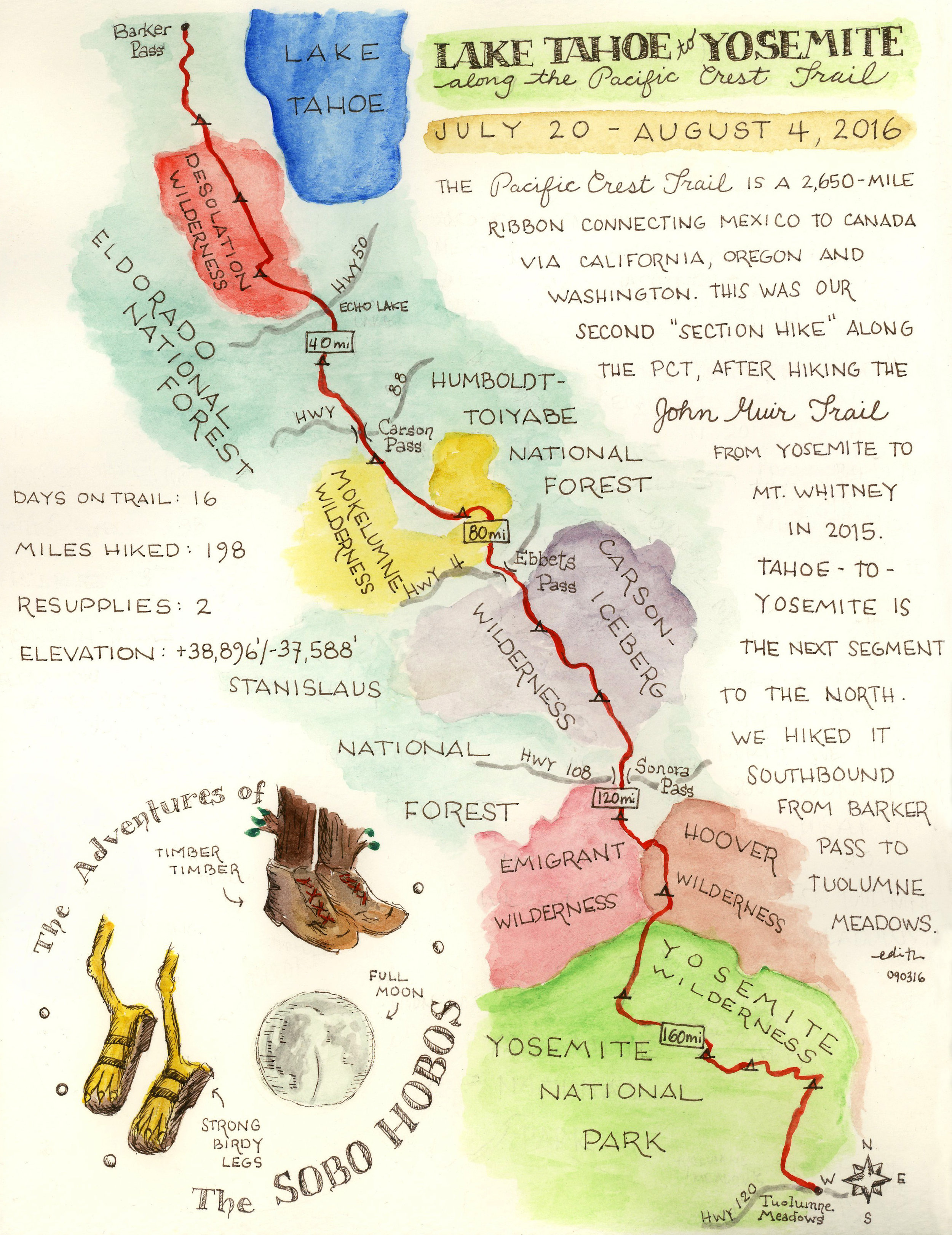

For transportation, we were two parties coming from Los Angeles and Sacramento without any friends or family foolish enough to offer us a drop-off or pick-up. The three of us met at trail’s end at Whitney Portal and left one car there. From there, we drove to Sequoia National Park on the west. We then did the same drive again a week later. In between we hiked a few dozen splendid miles.

Our 7-Day Itinerary (September 8-14, 2019)

But first, a note about mileage. Mileage on trail signs and maps is notoriously variable and unreliable. Mileages listed below are according to our trusty Garmin eTrex 30 and include the occasional off-trail jaunt to check out interesting features or scout a campsite.

Day 0

Our two parties met at Alabama Hills Cafe in Lone Pine and enjoyed a hearty I’ll-be-dreaming-of-this-meal-on-the-trail kind of breakfast. We left one car at Whitney Portal, then drove to Sequoia National Park. We camped at Lodgepole Campground (reservations recommended).

Day 1- Crescent Meadow to Bearpaw Meadow (11.7 miles)

We picked up our permit at the Lodgepole Visitor Center, parked our car near the Giant Forest Museum, and took the shuttle to the trailhead at Crescent Meadow (6,680’). Passing through the Giant Forest in the first part of the trail offers the only chance along the HST to commune with giant sequoias. Views of Moro Rock and the glaciated peaks of the Great Western Divide appear almost immediately upon hitting the trail, as the trail moves through moderate cover under pine, oak and cedar. Meandering along, with views constantly changing, we crossed Panther, Mehrten and Buck creeks. Having heard that Bearpaw Meadow was nothing to write home about, we had intended to camp at Buck Creek, but with the limited spots suitable for camping all taken by the time we arrived, we forged ahead to Bearpaw Meadow (7,820’). We were one of only two parties who camped there that night, and with roomy sites, a water spigot, and plenty of downed wood to make a fire, we were quite pleased with our first night’s camp.

Day 2 - Bearpaw Meadow to Big Arroyo Canyon (11.7 mi)

We started the day with a short but steep climb out of heavily-forested Bearpaw Meadow backpackers’ camp. The High Sierra Camp, located up the trail just as the views open up, was heavily damaged during the wet 2018-2019 winter and was consequently closed for the season. A small crew of NPS staff were working to rebuild.

The trail then descends through patchy forest and leads to a dramatic canyon of exfoliating granite slab, eventually crossing the narrow gorge at Lone Pine Creek (7,400’) over a sturdy bridge from which hikers can spy the mangled remnants of the bridge’s prior incarnation strewn precariously downstream. A steady ascent along exposed trail begins and doesn’t let up until Kaweah Gap some 6 miles and 3,000 vertical feet ahead. Fortunately, though the ascent itself is breathtaking, so are the views.

This was one of my favorite days of the hike, with jaw-dropping views and stunning rock formations sculpted by water overshadowed by even more impressive granite walls towering above. We lunched at Hamilton Lake (8,235’), a popular camping spot with a one-night camping limit. Continuing our ascent, we came across a portion of blown-out trail we had heard and read much about, which earlier in the hiking season presented a real challenge for hikers. A crew of two Sisyphus-like rock movers was hard at work fixing the trail. We offered them Sour Patch Kids (which they called “SPK”) as thanks, and they accepted then with excitement. Wispy clouds began to form as we moved through portions of trail blasted through vertical cliffs. The wispy clouds gave way to fog as we moved through wildflower-carpeted slopes, and by the time we arrived at Precipice Lake, we were socked in completely and the lake was fully obscured. Over the next few minutes the sun and fog danced a tug of war and we got a few dramatic glimpses of this beautiful lake and its surrounding cliffs. Passing a few small tarns in a wide verdant valley, we finally made it to Kaweah Gap (10,740’), but not before encountering two fast-moving pikas collecting vegetation among the rocks and seeing the plumpest marmot we have ever seen. The temperature had dropped a great deal since our relaxing lunch at Hamilton Lake hours before, and it was too cold to stay in exposed Nine Lake Basin, where we had planned to camp. We soldiered on another couple of downhill miles, finding a site nestled among trees and rocks along Big Arroyo to call home for the night.

Day 3 - Big Arroyo Canyon to Moraine Lake (9.3 mi)

We awakened to the sound of hooves hitting rocks on the trail as about a dozen horses and mules passed close to our camp. Back on the trail we descended a mile or two toward Big Arroyo Junction (9,560’) before ascending about 800 feet along a southwest-facing slope affording excellent views of the Great Western Divide across the canyon. We took a lunch break along this rocky slope just as our descent began toward the sandy meadow at the junction with the Moraine Lake trail. Here most HST hikers temporarily leave the HST and detour to Moraine Lake (9,302’), which is where we spent our third night. We set up camp (more of a homestead, complete with a clothesline, kitchen and communal fire pit), and spent the evening around the fire exchanging trail stories with other hikers.

Day 4 - Moraine Lake to Whitney Creek (13.6 mi)

Leaving Moraine Lake, the trail descends several miles to Kern Canyon (6,730’). Passing the remnants of an old cabin just past the lake, views to the north soon open up to reveal delightful Sky Parlor Meadow and its pastoral grassland, with the Great Western Divide and the Kaweahs dominating above. We soon rejoined the HST and began a steeper descent down to Kern Canyon, enjoying an occasional stop to stick our noses in the bark of Jeffrey pines that dot this part of the trail — the bark smells just like sweet butterscotch! Back in lower elevations, in the land of manzanita and juniper, we reached the bottom of the canyon and turned due north.

Our next stop was Kern Hot Spring, most conveniently located at the halfway point of the HST. After a quick soak and a trail shower complete with a much-needed hair wash, we continued north along the Kern River for a few miles. Along the way, I took an unintentional dip (read: slip and fall) in Rock Creek. Fortunately, temps in the canyon were warm-ish and my wet clothes had a chance to (almost) dry by evening. Late in the afternoon, we came upon Whitney Creek, a wide crossing whose cold, rushing waters were uninviting after a long day of hiking. We found a lovely place to camp just before the creek and above the trail, where we enjoyed a quiet evening by the campfire.

Day 5 - Whitney Creek to Wallace Creek (7.1 mi)

Fording Whitney Creek in our camp shoes first thing in the morning was a quick and effective way to shake off any grogginess. Continuing along the Kern River, we soon forded Wallace Creek, knee-high and fairly swift even this late in the season. We took a break at Junction Meadow and were joined shortly by a few hikers we had been leap-frogging with for the past couple of days. A nearly 3,000-foot climb started thereafter, rising above the canyon to reveal views of the Kaweah Basin and Chagoopa Plateau to the southwest. The climb is exposed and dry, making for a slog, but the views improve constantly and offer many opportunities for breaks. Near the top of the climb we joined with the John Muir Trail, bringing us to terra cognita once more — though it had been four years since we last traveled this part and it took some reorienting to find our bearings. We crossed Wallace Creek (10,400’) and found a lovely spot to camp for the night, complete with a large rock “table” right in the middle of camp. Here we enjoyed “trail happy hour” treats including pine nut and black cumin seed hummus served with warm tortillas freshly sautéed in olive oil, and the bartender special for the evening, SPK margaritas.

Day 6 - Wallace Creek to Guitar Lake (8.7 mi)

In the morning we awoke to the lowest temps of the trip. Ice crystals formed when I went to fill a pot of water for boiling, yet spirits were high as we had a fairly short and very pretty day of hiking ahead of us. We had a brief ascent up to Sandy Meadow and soon arrived to Crabtree Meadow (10,640’), where we took a lunch break with fellow hikers we’d been getting to know the previous days. From there it was a short distance to Timberline Lake, a place we fell in love with when we did the JMT. We bushwhacked to get to the opposite side of the shore and took a long, restful, sun-soaked break, taking in the views and later exploring the labyrinth of seemingly hand-sculpted waterways that feed the lake. Guitar Lake offers no shade and we had no reason to arrive there too early. Eventually, we peeled ourselves from Timberline Lake and continued on, entering Whitney’s other-worldly rocky terrain, and we set up camp north of the trail along Whitney Creek. We were well above and a distance away from Guitar Lake to avoid its cold, damp microclimate — and frankly, the congested tent village that forms there daily during the high season. We had an early dinner on a hill overlooking both Guitar and Timberline lakes, and we were in bed by 7pm in order to leave camp by 2am for a sunrise ascent.

Day 7 - Guitar Lake to Whitney Portal (15.9 mi)

We arose at 1am under the full moon. It was surprisingly pleasant out. Despite the harshness of the alpine zone we were now in, it was significantly warmer than the chilly nights we spent Big Arroyo or Wallace Creek. At 2am, ours were the first headlamps on the trail that day. We passed the tent village, and then a few other campsites strewn on either side of the trail. We had nearly 5 miles and 3,000 feet of ascent to cover, and though we had been acclimating over the past week, our lungs are accustomed to breathing at sea level and we knew we were in for a challenge. There is 43% less oxygen on the top of Mt. Whitney than at sea level, and we knew that sleep-hiking in the ever-thinning air meant we needed to give ourselves plenty of time to take it easy.

The full moon illuminated the trail and surrounding landscape, and it was easy to make out features all around us. As we ascended switchbacks, we began to see a faint trail of headlamps — first one, then a few more, until eventually there was a steady stream of headlamps making the slog. We left our heavy packs at the trail’s junction, some two miles from the summit, bringing just a few items with us for the last stretch. During the last mile to the summit we got a few glimpses of the eastern horizon beginning to glow an intense orange as we passed “windows” along the trail — spaces between the crags and needles that open up suddenly to reveal Owens Valley 10,000 feet below. The sky began to light up, and soon the majestic mountains and deep canyons around us were bathed in soft pink light. We arrived at the summit with 10 minutes to spare, and soon the sun reared its head over the horizon in an intense red-orange. It was stunning. This was our third time atop Mt. Whitney, but it was entirely new and epic for us to experience it this way. We fired up our stove and boiled water for tea and miso soup as other hikers began to arrive on the summit. We cheered them on and got a few of them to smile. On the way down, we passed dozens of weary hikers as we descended to collect our backpacks. By the time we arrived at Trail Crest (13,650’) around 9am, day hikers who had started their hikes at Whitney Portal in the middle of the night were beginning to arrive, and for the rest of the day we were no more than a stone’s throw away from other hikers for much of our descent.

Coupled with our lack of sleep and ultra-early rising time, losing 6,000 feet over 11 miles exhausted us more than we had expected, and the next few hours seemed to stretch on forever. We took a restorative lunch at Mirror Lake and continued our descent, finally arriving at Whitney Portal (8,325’) in the early afternoon. We snacked on an order of french fries piled high on a big plate, and were pleased to find the car we parked a week earlier just sitting there, patiently waiting for three smelly hikers to pile in and drive off. We headed to Bishop, where we checked into a motel, took a well-earned shower, had a satisfying dinner at Mountain Rambler Brewery, and slept like babies. The next morning, we had breakfast at the famed Schat’s Bakery and then began a meandering drive back to Crescent Meadow, via the more scenic route of Highway 178 through the mountains.

Total mileage: 78

Elevation: +13,354 ft / -11,854' ft

History of the High Sierra Trail

Remember that historical rabbit hole I mentioned earlier? Let’s drop down for a quick visit.

Sequoia National Park was established in 1890, protecting the western edge of today’s park boundaries as a means to preserve the giant sequoia. Interest to expand its boundaries eastward emerged almost immediately, but preservation under the National Park System of the the Great Western Divide, Kaweahs and Mt. Whitney would not occur until 1926, when legislation grew the park to nearly triple its original size.

The newly added area was entirely free of roads and had only one trail — and a very difficult one at that. The question facing park managers now was how to connect the two parts of the park, split by the formidable Great Western Divide. In charge of determining an answer to this critical question was Park Superintendent John White, who decided that the ribbon connecting the home of the world’s largest living organism on the west with the highest point in the continental US on the east would be a backcountry trail. He further decreed that a road would never be built, and that the land would be preserved as wilderness for future generations.

The decision to build a trail was now made, but the rugged terrain stood in the way as a major obstacle to realizing the vision. Shortly after White’s decision, and with no design yet in place, crews began work at Crescent Meadow on a 4-foot wide trail which was to have no more than an 8% grade. Challenging topography appears within a mile of the trailhead, and in 1928 a ground crew was sent to study the route choices. Their charge was to maintain a gentle grade while limiting scarring of the landscape, particularly along granite slopes. A highway engineer by the name of John Diehl, who around the same time was overseeing work on the Generals Highway which winds through the western section of the park, was assigned to the High Sierra Trail project and was charged with overseeing its construction starting in 1929. With the first section of trail completed, he was to determine how to continue the trail from Mehrten Creek and connect it to Mt. Whitney. Studying the various proposed approaches, he decided that the Great Western Divide would be crossed via a route that went through the Hamilton Lakes area up to what he called the “Kaweah Gap.” One of the most challenging trail-building sections would be Hamilton Gorge, which required a trail to be cut out of sheer rock along vertical cliffs. This route was nevertheless favored over two other alternatives because it was lower in elevation and would provide better connections to existing trails on the other side.

The Great Depression began just as the first trail-building season closed, but even as Americans sank deeper into economic turmoil, efforts to build the HST did not halt. Over the subsequent two years, work on multiple segments of the trail continued at a steady pace, and at one point separate crews were working simultaneously on west side, on the east side inching up the western edge of Mt. Whitney to connect the HST to a US Forest Service trail being built on the eastern slope, and in the middle, along Kern Canyon. By 1932 the trail was almost complete, with the last remaining gap at Hamilton Gorge. An incredibly ambitious suspension bridge was built spanning the gorge, requiring literally tons of material to be carried over inconceivable distances by trail crews and mule trains. The bridge lasted only 5 years before being destroyed by an avalanche. An alternate route was built in its place, blasting ledges and a tunnel to hug the gorge instead of spanning it, and the HST we know today was finally complete. In 1934, the High Sierra Camp at Bearpaw Meadow was built and has been in operation since, adding another desirable destination to this already attractive trail.

Despite harsh conditions and the absence of virtually any safety equipment during its construction, the High Sierra Trail was completed with no fatalities. That it was envisioned as a roadless wilderness at a time when the US had a population only 1/3 of what it is today, and California had 1/8 of the residents we now do, is nothing short of remarkable. Almost a century later, the HST continues to offer an exceptional backcountry experience and a transcendent way to relish the many gifts that the Sierra has to offer.